Emily Furner and William Eggington, Linguistics and English Language

When a new word premieres in a publication in the English language, the word is normally followed with a definition (hereafter gloss) that defines or restates its meaning1. But generally, words will eventually stop being defined as readers come to understand the meaning of the word. In other words, when readers “accept” a word into their vocabulary, the practice of including definitions with newer words becomes unnecessary. In this study, I explored the possibility of using corpora to determine when words stop appearing with definitions, thus signaling when these new words became “accepted” into American English.

My research analyzed the average amount of time required for a new English word to become generally accepted into common publications. To search words that debuted into the English language from 1910–2010, I used one of the largest digital corpora available to the linguistic world—Google Books: American English (hereafter, Google Books), a corpus that contains over 155 billion words created by Dr. Mark Davies. I selected ten randomized English words per decade from 1810–2000 that appear in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) Online and then searched for each word in the Google Books corpus in order to measure the time period that it took for the new words to appear without their definitions attached to them. The corpus results for each word were hand-researched and kept track of using data tables that contained fields for each publication in which one of the words appeared. Publications were tracked over time, and also were screened to determine what type of definitions accompanied the words.

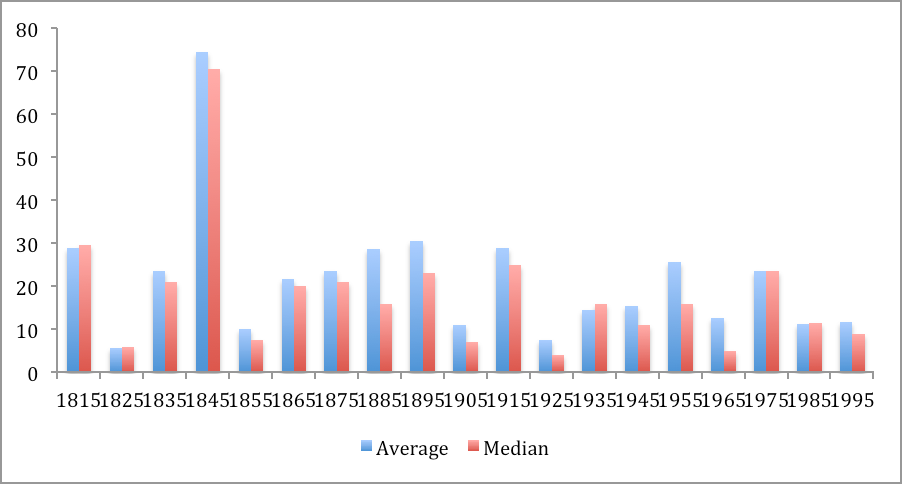

To analyze the data, I found the mean and median time per decade that a word took to appear in a publication without a definition. The results of these calculations are shown in Figure 1 (below). From the results, there is no clear trend of consistently either increasing or decreasing the average number of years a word needed to lose a gloss over time. In fact, the average seems to fluctuate quite a bit, climbing as high as 74.5 years in 1845 and falling as low as 5.67 in 1825. The total average throughout all the decades was 21.54 years. However, during the research phase, I noticed several trends relating to word type and genre that affected the timeframe of gloss inclusion for specific words. By comparing word genres with each other, it seemed apparent that genre and word type heavily affect the way glosses appear, which explains why no clear trend appeared in the raw averages and medians of these words.

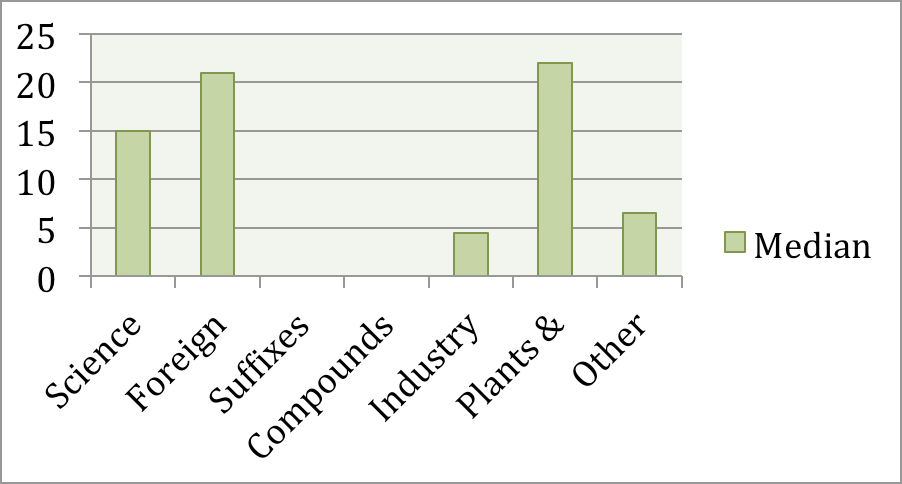

After realizing that word genre affected the time frames that words were glossed, I went through each of the 190 words in this study and categorized them according to their definitions in the OED. If the OED mentioned that a word came from Italian, for example, then I classified it under the “foreign word” category. There were, of course, some words that did not fit into the main six categories that I was looking at (science, foreign words, words with suffixes, compound words, industry words, and plants and animals). These words were most often slang and/or fashion words, and were put into the “other” category. Once I found the word categories, I compared the median time frames of each category against the varying genres (see Figure 2 below). The medians matched the trends I saw in the raw data. Suffixed words, as well as compound words, were not defined over 50% of the time, meaning that their median was zero years needed to drop a gloss. Plants and animals took the longest time to drop their glosses, followed by foreign words and then science words.

As an editing minor, I hoped through this study to be able to find a generic average amount of years a publisher could safely include a gloss for new words in the language. However, the time period for each decade fluctuated quite a bit, with no real trends occurring in the data. After researching almost two hundred randomized words, I found that the average amount of time a word took to lose its gloss in the publishing tradition was 21.54 years. However, this average does not take into account word type, register, or publication genre, and these three factors were found to significantly affect whether the word appeared with a gloss or not. Having a rule about glosses for all genres and word types would oversimplify the process of deciding whether or not to include a gloss in the publication. Further research into specific genres might yield more concrete guidelines for gloss inclusion.

The implications of this study are far-reaching when the results are applied to dictionaries. Because there are significant differences between genre, word type, and register, dictionaries should carefully consider the types of words that they define. From the data, it would make sense to have specialized dictionaries according to word genre. This already is in practice, with science and chemical dictionaries leading the way. However, dictionaries for fashion words or other words that tend to enter and leave the language quickly might need to have their own dictionaries as well.

Figure 1 – Graph of the Average and Median by Decade

Figure 1 – Graph of the Average and Median by Decade

Figure 2 – Comparison of Medians by Word Category

Figure 2 – Comparison of Medians by Word Category

1 The following are examples of words that appeared with glosses. All examples are taken from the Googlebooks corpus, accessed 14 June 2012: Relative clause: “Mecillinam, which is a non-acylamino derivative of 6-aminopenicillanic acid.”; and “Or” phrase: “The author of the Rasakollola, Din Krishna Das, was a Vaishnava or quasi-religious idler at the great temple of Jagganth at Puri.” Other glosses found in this research included appositions, charts, diagrams, footnotes, pictures, etc.