Student: David Seay, Faculty Mentor: Dr. Robert Brandt (Vocal Performance Department)

INTRODUCTION

Vocal performers of the past century appeared to be unaware of Bach scholars’ discoveries regarding ornamentation. Despite scholars having written more about ornamentation than any other performance-related topic, recordings from 1945-1975 indicate that vocalists performed Bach’s music with “basic principles [of ornamentation] but took little account of scholarly detail or stylistic specifications.” 1 It was also discovered that despite Bach scholars’ efforts to reach their vocalist-audience, discussion on how to ornament the recitative – a music form most unique to vocalists – was largely overlooked.

Now 15 years into the 21st century, this ornamentation link between scholars and vocalists is due for a revisited analysis. Additionally, the lack of past scholarly discussion on ornaments in Bach’s vocal recitatives necessitates an analysis on ornamentation in this music form. In response to these needs, this study explores the extent scholarship on Bach ornamentation has influenced 21st century performance-trends of Bach’s recitatives. A number of variables will be considered: the number of performed ornaments per singer, and each ornament’s type, length, weight, and beat-relation.

Now 15 years into the 21st century, this ornamentation link between scholars and vocalists is due for a revisited analysis. Additionally, the lack of past scholarly discussion on ornaments in Bach’s vocal recitatives necessitates an analysis on ornamentation in this music form. In response to these needs, this study explores the extent scholarship on Bach ornamentation has influenced 21st century performance-trends of Bach’s recitatives. A number of variables will be considered: the number of performed ornaments per singer, and each ornament’s type, length, weight, and beat-relation.

METHODOLOGY

21st century recordings of Bach’s “St Matthew Passion” were collected for this study, and a comparative analysis was conducted on all recitatives performed by the tenor-evangelist. The 16 collected recordings represent nearly one recording per year from 2000 to 2015. 3 of the recordings used Bach’s earlier manuscript for performance, the BWV 244b (a manuscript with significantly less written-in ornaments). The performing evangelists using Bach’s earlier manuscript of the work, BWV 244b, were Petzold, Gilchrist, and Daniels. Every ornament performed by each Evangelist was documented with four specifications: the type of ornament, the length of the ornament, the degree the ornament was stressed, and the ornament’s relation to the beat.

After documenting the details of every single performers’ ornaments, each vocalist’s approach to ornamentation was compared and contrasted to discover the commonalities and differences among them. The results were compared to principles of ornamentation put forth by past and modern scholars, to determine if vocalists’ ornaments aligned with traditional or modern views of ornamentation.

RESULTS

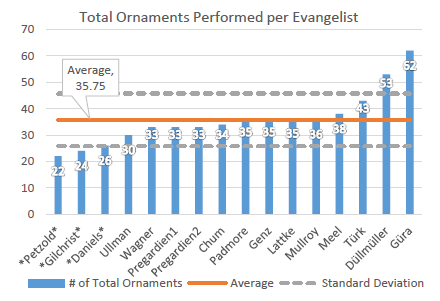

Of the 16 evangelists studied, 103 different ornaments were performed while singing the recitative movements of the St. Matthew Passion. Güra sang the greatest number of ornaments, totaling 62. Petzold sang the least number of ornaments, totaling 22. The average number of ornaments sung per Evangelist was 35, with a standard deviation of 10.

The most common ornament sung in the Evangelist’s recitatives was an appoggiatura with a long length (meaning half the length of the note it is connected with), sung on the beat, with emphasis. The other ornaments that appeared in the recordings were pre-beat appoggiaturas (3 occurrences), post-beat appoggiaturas (3 occurrences), a between-beat appoggiatura (1 occurrence), rising on-beat appoggiaturas (8 occurrences), rising pre-beat appoggiaturas (8 occurrences), a double appoggiatura (1 occurrence), ascending slides (2 occurrences), descending slides (6 occurrences), and 1 trill.

The most common ornament sung in the Evangelist’s recitatives was an appoggiatura with a long length (meaning half the length of the note it is connected with), sung on the beat, with emphasis. The other ornaments that appeared in the recordings were pre-beat appoggiaturas (3 occurrences), post-beat appoggiaturas (3 occurrences), a between-beat appoggiatura (1 occurrence), rising on-beat appoggiaturas (8 occurrences), rising pre-beat appoggiaturas (8 occurrences), a double appoggiatura (1 occurrence), ascending slides (2 occurrences), descending slides (6 occurrences), and 1 trill.

Regarding the weight of ornaments performed, special focus was placed on normal on-beat, descending appoggiaturas. The sum of all such appoggiaturas sung by the evangelists was 536, an average of 33.5 per singer. Of these appoggiaturas, 71 (13.2% of the total) were sung with equal emphasis to their following note. The average number of such equally-weighted appoggiaturas per singer was 4.44, with a standard deviation of 4.77.

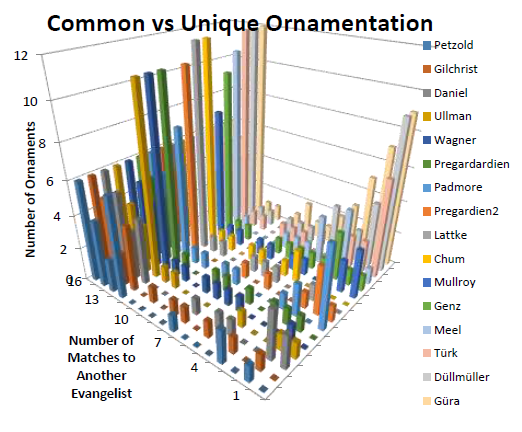

Regarding the commonality of ornaments among the evangelists, 27 of all 103 ornaments performed were sung by at least 13 vocalists. There were 53 ornaments that were sung by only 3 vocalists. 33 ornaments were uniquely sung by only 1 vocalist. The number of individually unique ornaments sung per singer is as follows: Güra (9), Düllmüller (9), Türk (6), Padmore (5), Mullroy (3), Daniel (2), Ullman (1), Pregardien-son (1), Gera (1), Meel (1), Chum (0), Latke (0), Pregardien-father (0), Wagner (0), Gilchrist (0), Petzold (0).

DISCUSSION

There are significant changes taking place in the interpretation of ornamentation in Bach’s recitatives. Although Bach scholarship in the early 20th century called for a strict and somewhat rigid interpretation of ornamentation in Bach2, scholars in the late 20th century and modern scholars now advocate for a more flexible approach3. Although 20th century vocalists were found to be largely uninfluenced by their scholarly peers, the evidence of this study suggests that modern vocalists are starting to follow the trend of free interpretation. Of particular significance are the types of ornaments performed by each vocalist. Traditional scholarship says that free ornamentation in Bach recitatives should be performed moderately, and the only ornament to be used should be traditional appoggiaturas4. However, only half of the vocalists studied here held true to this tradition. The other half used alternative (pre-beat and post-beat) appoggiaturas, slides, double appoggiaturas, and there was even an occurrence of a trill. In addition, although 12 of the singers performed 36 ornaments or less (a moderate amount), 4 vocalists performed a more sizeable amount of ornaments, thus breaking the tradition of only “moderately ornamenting” in recitatives.

Additional evidence from this study suggests a modern trend among Bach vocalists who approach ornamentation more flexibly. More than a quarter of all ornaments performed (38 to be exact) were individually unique to a specific vocalist. It cannot be said that the majority of vocalists are taking part in this trend, because less than half of the vocalists performed one of these unique ornaments, and of those vocalists, only 3 performed a significant amount of unique ornaments (4 or more). But the fact that there are any vocalists performing unique ornaments suggests that modern scholarship  advocating a free approach to interpretation of ornaments is starting to take hold among vocalists.

advocating a free approach to interpretation of ornaments is starting to take hold among vocalists.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the divide between scholars’ and performers’ approach to Bach ornamentation performance practice appears to be thinner than in decades past. This study’s findings, that only a portion of singers performed ornaments that were individually unique, suggests a parallel between scholars and vocalists in the development of their interpretation of Bach ornaments. Just as scholars past have long argued for a strict interpretation of ornamentation in Bach’s music and only scholars of recent years have raised a critical argument for free interpretation, so, too, are the majority of singers holding to the traditional ornamentation practice and only a small portion in recent years are ornamenting in Bach with a more free interpretation. Regardless, it is of great significance that any singers are performing ornamentation more freely in Bach’s music, because, according to studies in the past, there were none to be found in the past century.5 This suggests that modern scholarship is beginning to take hold among vocalists. We may find that the number of 21st century vocalists utilizing a more free approach to ornamentation may continue to increase.

1 Fabian, Dorottya. “Interpretation II: Ornamentation.” Bach Performance Practice, 1945-1975. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003. 135-168. Print.

2 Neumann, Frederick. Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-baroque Music: With Special Emphasis on J.S. Bach. Princeton, 1978. Print.

3 Butt, John. “Ornamentation.” Oxford Composer Companions: J.S. Bach. Ed. Malcolm Boyd. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. 350-354. Print.

4 Donington, Robert. A Performer’s Guide to Baroque Music. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1974. Print.

5 Ibed. Fabian, “Ornamentation.”