Andrew Bashford and Dr. Mark Tanner, Linguistics and English Language

English teachers’ primary goal is to help their students use English as a means of communication, self-expression, and transaction. Of course, learning a second language is not a spontaneous process: it requires study, practice, and meaningful feedback. In fact, one of the teacher’s most essential roles is that of providing feedback to students, often in order to correct errors and guide the students’ learning. This current study deals with the feedback that teachers provide when their students make errors in speaking—oral corrective feedback, or OCF. While much work has been done to investigate the most effective ways of giving OCF to students, surprisingly little has been done to investigate how effectively these research-based recommendations have made it into the classroom. In order to gain a better understanding of how—or whether—teacher practices are influenced by recommendations in the research literature, we created a survey to ascertain both what teachers do in the classroom and what beliefs and external factors drive their practices.

Our survey was a 29-item questionnaire that was administered online to English teachers in English-speaking countries (ESL) and in non-English-speaking countries (EFL). It included questions about the respondents’ education and experience as well as asking about the types of students they teach (advanced learners, beginners, children, adults, etc.). It then provided respondents with questions about which OCF techniques they use most frequently, what circumstances condition their use of certain OCF strategies, and what beliefs have influenced their approach to providing OCF. Nearly 300 teachers from around the world completed the survey. Of those who completed the survey, 71% identified themselves as teaching in an ESL environment while the remaining 29% identified themselves as teaching in an EFL environment. Years of teaching experience varied widely among the respondents with 30% having more than twenty years of experience and 9% of respondents having less than a year of teaching experience with the rest falling in between. Most (68%) teach English for academic purposes to university students or to college-bound learners. After collecting the data, we began to examine the responses and to look for trends in the practices of English teachers worldwide.

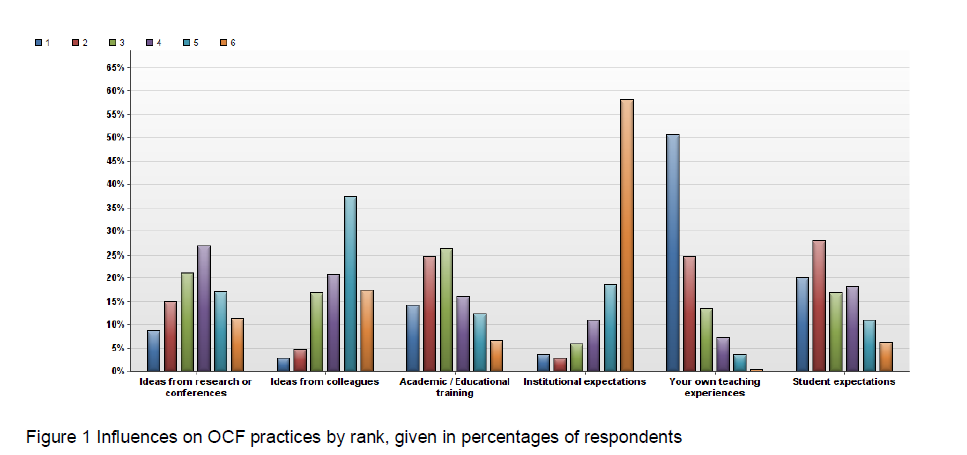

Upon looking at the results, it was readily apparent that the teachers who participated in the survey employ a wide variety of OCF techniques: every technique was rated as being used “some of the time” more than any other frequency, and “always” or “never” ratings were very rare. Teachers also report focusing their feedback most often on grammatical and word errors rather than on other elements of speech such as intonation, speaking rate, or contextual appropriateness. Further, participants most often ranked their own teaching experience as being the most influential force in their OCF practices, followed by student expectations, training, ideas from research and conferences, ideas from colleagues, and institutional expectations.

In our effort to discover what drives ESL and EFL teachers’ OCF practices and to learn how effectively research influences teachers’ habits, it is clear that their personal experience with teaching is the primary influence in their habits and practice. Unfortunately, these data show that teachers, while leaning on their own experience, are not finding great success in applying research-based recommendations related to what types of feedback to provide or what types of errors to correct. In fact, the data reveal little systematicity in teacher practices, suggesting that, perhaps, more could be done to ensure that research findings are conveyed to teachers and implemented in classrooms in order to provide the most focused, effective, and worthwhile feedback to students. Of course, it’s also possible that the lack of well-defined patterns highlights a need for further research into the circumstances and situations that influence OCF practices. That is, while the current data show little systematicity in OCF practices, further research could reveal patterns that the current survey is unequipped to show.

From the start, this study has aimed to lay a foundation for further research. By providing a glimpse into the philosophies that drive teachers’ classroom practices, this study has shown that teachers use a wide variety of corrective strategies in order to address a relatively focused spectrum of spoken errors. It has also shown that teachers don’t report being influenced by research as much as by their own experience, their students’ expectations, or by teacher-training programs. Thus, this study is informative primarily in the way that it provides foundations for investigations into how teachers decide whether certain corrective moves match certain classroom situations or into how research-based recommendations can be more effectively implemented in the classroom. By opening a discussion on the ways teachers report offering OCF to their students, this study opens the way for further, deeper investigations into the ways that academic research and classroom practices can interact more effectively in order to provide students with the most worthwhile education possible.