Brittany Strobelt, Kylan Rice, Dr. Matthew Wickman, and Dr. Billy Hall, English Department

The continual digitalization of society has not only permeated research in the Humanities, but is constantly revealing just how crucial it is to the Humanities’ future. Whereas research in the Humanities is normally limited to a very narrow dataset, digital humanities tools allow for macroanalitic research—research that can analyze vast amounts of texts all at once. The database produced by our project can do just that. Because scholars’ such as Ted Underwood, Matthew Jockers, Franco Moretti, and others at the Stanford Literary Lab have focused extensively on macroanalysis of novels, we envisioned and designed a project focused specifically on poetry—a century’s worth of British poetry no less. Thus, through identifying certain metadata from within a large set of eighteenth-century British poetry, specifically the themes and genres of the poetry, our database provides the means to explore patterns, trends, and variations in such poetry. However, exploring the genre of poetry was not intended to be the end goal; rather, we believed that this line of inquiry might serve as a means to opening a profound set of questions that could account for technical patterns in eighteenth-century poetics, clarify classical influences on style and form, illuminate alternative historical narrative concerning socio-cultural relationships, and help track the evolution of ideas across an important moment in intellectual history. Moreover, we intended this project as a foundation upon which future projects invested in exploring eighteenth-century poetry could be built.

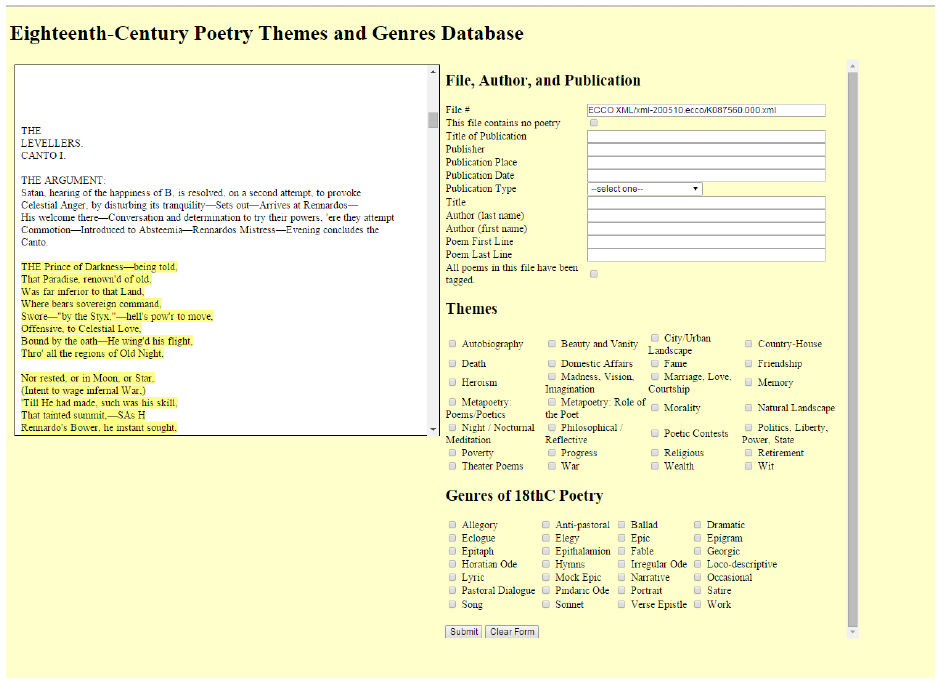

At the outset, we had a general idea of what we needed to produce, but that idea only became clearer as we delved further into the project itself. First of all, we sought poetry with which we could populate a database. We ultimately selected our initial dataset from the ECCO-TCP project; from the original 2300 ECCO-TCP files, we extrapolated a smaller set which still contained well over 2000 individual poems. In the midst of the extrapolation process, we also worked to develop a list of criteria to categorize and label the poetry set. But in order to organize a large dataset of poetry into manageable themes and genres, we needed to create a php database and html interface with the relevant metadata, and so we enlisted the help of Jarom McDonald and Jeremy Browne of the Office of Digital Humanities. Once this database was running, we began to tag the poetry (all of the poetry tags can be seen in the image below).

Initially, we planned our project in three steps: first, create a corpus full of eighteenth-century British poetry; second, analyze the corpus by utilizing big data algorithms; and, third, produce corresponding visualizations. Due to the complexity of constructing a corpus, we have focused primarily upon our first step. As noted, we chose to utilize files from the Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) database that had been hand transcribed and marked up by the Text Creation Project. These files are offered free, and we hope to have access to the entire ECCO database in the future. Unfortunately, the ECCO-TCP files contain a conglomeration of poetry and prose files. At first, we thought we might be able to separate the poetry files by hand; however, we quickly realized the infeasibility of such a process. So Professors McDonald and Hall wrote a script that used the xml tags to separate all files that contained a line of tag (used in markup languages to distinguish poetry from prose). However, this did not account for poems embedded in prose, and it still left us with a great deal of sorting work. But through this setback, we were better able to identify what poetry we were seeking. We had to decide whether or not we wanted to include embedded poetry, but even then, we had to narrow down exactly what type of embedded poetry could be allowed. For example, we questioned the value of including a poem created by a novel’s character, recited poetry, and so forth. In the end, we believed that such refinements are important to the accuracy of our database to reveal trends and variations in eighteenth-century poetry. In addition, we realized that such nuances in the sources of poetry quite possibly could reveal interesting findings in the future about the actual poetry being produced during the eighteenth century in Britain. But this was not the only obstacle we faced. While tagging poetry, we also encountered inadequacies in our lists of possibilities for genres or

themes in the poetry. For instance, we discovered that our original list of poetic themes lacked the topics of progress, fame, and natural landscape, while our list of poetic genres lacked fables and portraits. But, once again, our process helped to refine our database, which will certainly impact our future results.

Our first attempt at such a large-scale project to detail genre within eighteenth-century British poetry and to discover its nuances and implications upon eighteenth-century British society was certainly ambitious, perhaps even a bit foolhardy given what we have learned. However, based on our discoveries and progress, the next iteration of the themes and genres in the database will be much better for the efforts. And we are not the only benefactors of our work. Because of our needs for access to a vast volume of poetry files, all of BYU is now able to access all of the metadata for the ECCO literature files. Thus, even though our project is still in progress, our accomplishments are not insignificant. We built and populated a database of poetry and even designed it to catalogue a searchable set of theme and genre criteria. Moreover, we discovered hindrances that can occur in such a digital humanities project. Such discoveries will aid in avoiding pitfalls in the future and will likely usher in more success. Additionally, our work initiated the process to negotiate access to ECCO’s much larger metadata collection of literature files, which opens new possibilities for future digital humanities projects at BYU. Therefore, our work thus far has already created a much stronger foundation upon which we and others can build upon in the future.