Catherine Johns and Dr. Brigham Daniels, College of Law

This project originally aimed to research tree richness and diversity using the Point Quarter method in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park but after the first day attempting to work, I learned how impossible the forest actually is. Having never experienced such a dense mountainous forest, not even the “impenetrable” in the description made me consider that working there would be so physically impossible. After talking with park officials, I quickly realized that all the work I wanted to accomplish and much more was already being completed by the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA). The combination of these two things led me to change the study location to Mabira National Forest. Mabira is Uganda’s last non-mountainous old growth forest and because it only houses monkeys and birds, rather than gorillas and other mammals like Bwindi, it is not nearly as funded or protected.

In agreement with the Point Quarter method, four sampling points were predetermined along a transect, forming four imaginary quadrants at each point. A nylon rope was used as the transect and the points marked at respectively 0, 33, 66, and 99 feet. The nearest adult tree (measuring at least 5cm in diameter) in each quadrant was measured for both diameter at breast height (1.3 meters) and distance from the point. Tree species and other observations, such as missing branches or death of specimen, were also recorded. Measuring tape and a caliper were used to measure the distances and diameters.

After obtaining a map of the forest divided into sectors—recreation zones, production zones, buffer zones, and strict nature reserve zones—I decided that the buffer zones would be the most threatened since they border the strict nature reserve zones and are not open to the public. Using Excel RandBetween formula, seven buffer zone sectors were selected (207, 208, 202, 192, 227, 226, and 221).

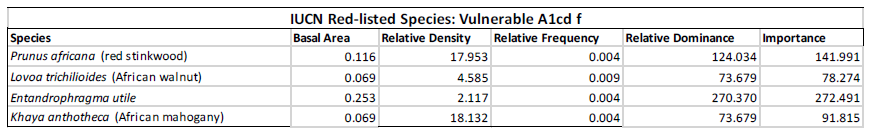

Of the 528 trees samples, 72 different species were recorded with the majority being native or non-invasive exotics. A native tree, Macaranga schweinfurthii, with a reputation as a recolonizer was found to have the greatest relative dominance (30.5%). However, Clausena anistata had the highest relative density (17.4%). We encountered seven Red-listed species identified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) during our work, including four Vulnerable A1cd species–Prunus africana (red stinkwood), Lovoa trichilioides (African walnut), Entandrophragma utile, and Khaya anthotheca (African mahogany). The most problematic tree we encountered was Broussonetia papyrifer (paper mulberry), which has been introduced from Asia and acts as a recolonizing invasive.

Table 1: Showing the density, frequency, dominance, and importance in regards to all IUCN red-listed species encountered.

Due to the unforeseen inadequacy of the Point Quarter method, which was developed for temperate and coniferous forests where vegetation is less dense, the data does not reflect well what evidence of encroachment we found. However, recorded species data was still useful in analyzing diversity and richness. Our identification and measurements of IUCN Red-listed species can be an important contribution to global understanding of at-risk trees and their species richness worldwide. Furthermore, evidence of encroachment outside of the method was found every day. Some areas had been clear cut in the 1980s and are still only occupied by non-climax plant communities growing under four feet. Other sectors became victims of encroachment only days within our data collection and in sector 192 we actually heard pit-saws from where we were working. On another day we ran into a poacher with fresh duiker meat in his bag. One day we hiked along the border of two different types of zones and noticed an unmarked path from one zone to the other that was not supposed to be there. As we hiked back later in the day a makeshift arrow had been attached to a tree near the path to identify it to other men looking to cut timber. In addition to this evidence of activity we noticed how many trails existed in each sector and how little control there was over it. Although we contacted each sector manager to notify them of what we found, there is simply not enough manpower to know about, much less control, everything that happens within the forest.

This project operated under the definition of encroachment as any act of illegal foraging within the forest. While working with members of the National Forest Authority (NFA) it soon became clear that they only regard clear-cutting a significant area as encroachment and define other smaller illegal acts as ‘disturbances.’ This difference may in part contribute to lack of proper funding for Mabira. Regardless, a more extensive report of this study was sent to the NFA for their records and for the hope that our extensive encounters with their ‘disturbances’ may aid in applying for additional government aid.

This project could have been improved with a more extensive knowledge of Uganda and its forests and by using a different sampling method. Not knowing about the vast collection of Bwindi’s unpublished data stuck in UWA was the biggest limitation but a most important discovery. Significantly less information is available for Mabira, so it became a much more suitable place for research. This opportunity opened my eyes to the realities of field work and even more so to the problems that can be solved by academic research done properly.