Hayley Darchuck and Jessica Callahan

Introduction and Literature Review

The 1960s showed marked improvements in the realm of decreasing the inequality gap between men and women. For example, government acts called for equal pay and protected women against discrimination. However, in the area of healthcare, women felt that there was a disconnect between themselves and the way that their bodies were being treated. For instance, doctors were mainly male at this time, and in 1970, women only made up 7.6% of doctors in the United States (Weisman 1998). These doctors spent little time with their patients and did not believe in sharing vital health information with their patients; doctors often thought that if they did so, their patients would fantasize health problems that they did not actually have as side effects of treatment (Morgen 2002).

Being spurred on by strides made in other areas of gender equality, women across the country began grassroots movements that started the women’s healthcare revolution. In 1969, four groups of women located in Chicago, Los Angeles, Boston and Washington, D.C. decided individually that they needed to take their health into their own hands (Morgen 2002). In Chicago a group of women called the “Janes” learned the abortion procedure to facilitate abortions for women during a time when they were illegal. Women in Boston came together to learn all they could about their own bodies, share that information with each other and then eventually publish Our Bodies, Ourselves, a revolutionary book. Further, Los Angeles was the birth of the self cervical exam, self help health for women, and the first free standing women’s clinic: the Los Angeles Feminist Women’s Health Center. Lastly, in Washington, D.C., women came together to lobby for open health information regarding female specific prescriptions, such as the pill (Morgen 2002).

Not only did these four groups pioneer the women’s health care issue during the latter half of the 20th century, but with their acts combined, they became the model of care for early women’s clinics. These clinic workers believed in open communication between doctor and patient, “for women, by women” healthcare, reproductive rights, self -help, education and free/low cost care. These clinics prospered for a time but became subject to outside forces that threatened to shut them down. Antiabortionist groups started vandalizing clinics that supported or performed abortions. Increased vandalism to the clinics called for increased funds to fix the damage. However, funds became limited in the 1980s due to Ronald Reagan’s presidency and his focus on “Reaganomics” (Morgen 2002).

Reaganomics introduced allocating less money to states than before in the form of block grants. These block grants were designed to group somewhat similar programs into the same funding groups while giving states the power to allocate the funds to the umbrella programs as they saw fit. Unfortunately for women’s clinics, they fell in the same block as child abuse and foster care. Most states were unwilling to allocate funds to women’s health clinics that may have supported abortion when they could allocate the funds to children in need instead. This, with decreased spending for Medicaid and Medicare, led to major budget cuts for women’s clinics and forced them to find funds from different sources while still trying to offer affordable healthcare (Morgen 2002, Moss 1996).

Around the same time clinics were facing decreased funds, hospital administrators realized the market potential of women. In 2002, for example, women controlled 66% of healthcare spending through their own healthcare and the decisions they made on behalf of their families (Scalise 2003). Hospital administrators appear to have realized that if they could attract women into their doors, the women would bring their family members when they fell sick and needed medical attention. This led to the co-optation of women’s healthcare, or the feminist health care goals being diluted by the economic priorities of the health care system. Thus, hospitals started advertising more heavily to women in general and even started to open women specific programs, wings and centers. They also added a wide diversity of services and options clinics usually did not offer, including mammography, plastic surgery and mental health services (Thomas & Zimmerman 2007). These services and programs were meant to attract the female patient. By adding extra services geared to women and advertising them specifically to women, hospitals drew more women into their doors and away from the clinics. For example, one study found that hospitals have increasingly shifted their priorities away from health care and towards profitability (Stratigaki 2004). Further, the executive director of women’s health in a Wisconsin hospital explained, “Women in midlife are a huge market segment that can be subdivided into as many as seven to nine distinct market segments. Adolescent and young women are another macro segment containing at least three to four unique segments” (Scalise). Clearly, hospital administrators have come to view women as a marketable population.

Because of the decreased funding towards clinics and the increased market potential hospitals discovered, we hypothesized that there would be a visual relationship between the decline of women’s clinics and the growth of hospitals that advertised and offered services towards women. We also proposed that the services offered in 2000, in both clinics and hospitals, would be substantially different from those offered in 1980. We believed that there would be an increased number of services offered and a variety of “new” services entering the women’s health marketplace as a result of increased competition for marketing to women.

Results

Overall Growth of Clinics

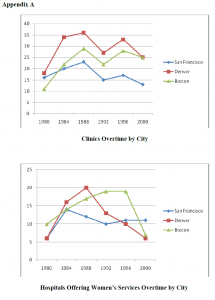

We found that the growth of clinics over time was consistent with our hypothesis. Each city followed the same pattern of growth, increasing in the 1980s until reaching its peak in 1988. Then, we found a sharp decline as the 1990s ensued, which could possibly be attributed to the effects of the Reagan era (Morgen 2002). The number of clinics increased slightly again after the Reagan administration ended and they tapered off by the end of the decade.

Overall Growth of Hospitals

We hypothesized that an increase of hospitals offering services to women in an area would be the result of a decrease in clinics in the same area. However, we found the number of hospitals offering services to women to be quite fewer than our expectations. We could possibly attribute the significant decrease in Denver hospitals to the splitting of the phone books into multiple Denver areas in 1992. This could have removed some hospitals from our records simply from those hospitals being recorded in another phonebook. Boston’s phonebook was also divided in the 1980s and may have had an effect by 2000 depending on which Yellow pages the hospital administrators decided to advertise in. Other factors that may have contributed to the hospital decrease could be the increased availability of the internet as a source of advertising for hospitals and possible hospital buyouts and mergers.

Growth of Services Offered

We found that, consistent with our hypothesis, the types of services offered in 2000 was a varied version of those offered in 1980. Although there was not a substantial shift in services, there are some important differences. In 1980, abortion and birth control were among the most common services offered, but in 2000, they decreased in popularity. Further, in 2000, pregnancy and birth control counseling became a new significant service offered. Additionally, in both 1980 and 2000, gynecology and obstetrics were the leading service offered to women, but while clinics offered the majority of these two services in 1980, obstetrics became more centralized in hospitals by 2000. Also consistent with our hypothesis, the number of services offered in hospitals increased from 1980 to 2000, including a doubling of hospitals that offered obstetrics and breast evaluations.

Discussion

Our results indicate that the growth of women’s health services in hospitals may not be as exponential as we previously thought it was. Previous research proposed that clinics were being overtaken and replaced by hospital programs because hospital administrators realized the marketing potential of women’s health services (Stratigaki 2004). However, because we found that both hospitals and clinics decreased from 1980 to 2000, we propose that there were many other factors at work in the women’s health industry. For example, one potential factor is the formation and growth of gynecological associations. Although we did not record the exact growth of these associations, there were many associations being formed during this time, especially in the 1990s. Perhaps when clinics failed due to funding problems (Morgen 2002, Moss 1996), gynecological associations were viewed as a new source of revenue; a physician could practice alone without the difficulties of developing and supporting an entire company of employees, as with a clinic. Further research could include the pattern of gynecological and obstetrical associations and the effects that they may have had on the women’s health industry.

An additional factor contributing to the pattern women’s hospital services growth is that of internet advertising. After the internet became more available for advertising, administrators for both clinics and hospitals could have opted to advertise on the internet instead of the phonebook. Because of this, the phonebook could be an inaccurate measurement of the actual growth or decline of clinics and hospitals. However, it should be noted that internet advertising became a significant form of advertisement specifically in 2004-2005, so the effects of it on our results may be small. In further research, internet advertising could be combined with phonebook listings in order to gain a fuller view of the pattern of change.

Similarly, hospitals buy-outs and mergers could be an additional variable. For example, some hospitals in Denver merged during the 1990s, causing a decrease in hospitals. Hospitals may have lacked required funding or could have simply combined their services to reach a fuller range of consumers. Further research could explore these implications.

The small expansion of and change in services in clinics and hospitals could be attributed to the continued need for birth control, obstetrics, and many other services. Women in 2000 use many similar services as women in 1980. However, there is a distinct division between clinics and hospitals and the services that they offered in 1980, and those that they offered in 2000. Hospitals seem to be slowly overseeing more and more services, while clinics become limited in the services they offer. For example, obstetrics, in 1980, was practiced primarily in clinics, but in 2000 was mainly a hospital service. This could show a development of divergent services in clinics and hospitals; they have different specializations. Further research could explore why clinics and hospitals specialize in different services, and why hospitals seem to be expanding some of the services that used to be offered primarily in clinics.

Conclusion

The women’s health industry continues to change and develop as the need for new services arises. This is clearly evident in the growth of maternity and birthing services, and breast evaluation services. As medicine advances, a new standard of care is introduced. With it, new services are validated and deemed necessary. Hospital services continue to expand, perhaps due to marketing profits, or simply a demand from consumers. However, we did not find our research to be consistent with that of previous research (Morgen 2002). Instead, we found that the number of hospital services for women actually decreased in Boston, Denver, and San Francisco during the years of 1980 through 2000. Further, the number of clinics only decreased slightly, and remained a significant portion of women’s services that were offered at the time. Thus, our results indicate that perhaps the marketability of women’s services was realized not only by hospital administrators, but by the entire women’s health services movement, including clinics. Clinics followed the market trend and were transformed to accommodate the demand for particular women’s services. Consequently, the clinics that are found in 2000 are very different from the “Janes” era in which clinics originated; clinics and hospitals entered the market economy of health services, and they continue to change as women’s services become more and more profitable. There are many factors that could have contributed to the many changes in women’s health services that we found. Further research could explore the effects of modern marketing strategies, alternative means of advertising, and the development of gynecological associations, on the women’s health industry.

References

- Morgen, Sandra. 2002. Into our own hands: The women’s movement in the United States, 1969-1990. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ Pr.

- Moss, Kary (1996). Man-made medicine: women’s health, public policy and reform. Durham, NC: Duke Univ Pr.

- Scalise, D. (2003). Defining and refining women’s health. H&HN: Hospitals & Health Networks, 77(10), 58-64.

- Stratigaki, Maria. 2004. The cooptation of gender concepts in EU policies: The case of “reconciliation of work and family.” Social Politics 11 (1): 30-56.

- Thomas, J. E., & Zimmerman, M. K. (2007). FEMINISM AND PROFIT IN AMERICAN HOSPITALS the corporate construction of women’s health centers. Gender & Society, 21(3), 359-383.

- Weisman, Carol. (1999). Women’s health care: activist traditions and institutional change. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Univ Pr.