Kendra Harris and Dr. James Swensen, Art History and Curatorial Studies

Giovanni Paolo Panini was a famous painter during the 18th century, and is mainly known as a vedutisti, or view painter. He is notable for his paintings of Rome, which often incorporated fantastical landscapes of the most renowned sites of the city.1 The purpose of this project was to recreate sixteen of Panini’s most famous works of art through photography, capturing the modern appearance of some of the most famous sites in Rome. By completing this research project, I have been able to document the ever-changing cityscape of Rome and continue Panini’s work of capturing the art and architecture of one of the world’s most important and dynamic cities.

In order to complete this project, I travelled to Rome as part of an art history study abroad program in May 2014. Our group stayed in Rome for nine days, and I was able to visit multiple locations every day. In order to recreate Panini’s works, I had to take into account the time of day, crowd size, vantage point, direction of light, and composition of each of his original paintings. I did this by taking a copy of the painting to the site, and then worked with these factors to photograph the setting of the original painting. Three issues emerged from Panini’s capricci style: he added objects or landmarks to his works that were not original to the site, painted with a rooftop viewpoint allowing the painting to have a more aerial perspective, and compressed the scale of the buildings in order to show them with a single perspective, which will hereafter be called a fish-eye lens composition.2 In order to work around the first issue, I chose the paintings that were the least fantastical. For the second, I asked many shop owners for permission to gain access to their upper rooms in order to achieve an aerial perspective, but was largely unsuccessful except for the Piazza del Popolo, where I was allowed into the upper balcony of the Basilica Santa Maria del Popolo – unfortunately, this photograph was still from the wrong angle. Lastly, for paintings with a fish-eye composition, I created a panoramic photograph to better mimic Panini’s styling.

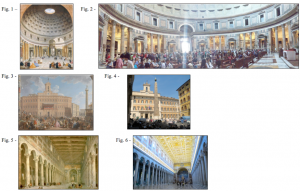

Of the original sixteen paintings, I was only able to recreate fourteen of them, as one was inside an opera house that was under renovation, and another was in a zone that I did not have access to. Of those fourteen sites, only eight of them turned out to be completely correct matches to Panini’s paintings. One of the sites that was the most difficult to recapture was Panini’s painting of the Pantheon, which is held to be his most famous. In this painting, Panini’s viewpoint is from across the door, situated in the altar area. However, Panini added an annex to the front of the altar area in order to have a place to stand and see the entire Pantheon; the ceiling of the annex can be seen in the top corners of his painting (Fig. 1). As I did not have the ability to make an annex in the Pantheon, the panoramic style of this painting was extraordinarily difficult to recreate, and I would consider my finished product to be subpar at best (Fig. 2). In addition, the lighting for this photograph was not correct, which led to a lens flare in the middle of the image.

One of the most accurate recreations is of the Piazza del Montecitorio (Fig. 3). In the original image Panini included the Column of Marcus Aurelius to the right of the Palazzo Montecitorio, which in reality is located two blocks behind where Panini would have been located to create this painting. Here, is it evident that Panini was creating a more fantastical image in order to incorporate more landmarks of Rome. However, the largest difference I found when I photographed the site was the Egyptian obelisk in the center of the piazza (Fig. 4). This obelisk is from Heliopolis, and was brought to Rome in 10 BC. However, it wasn’t moved to this piazza until 1792, some seventy years after Panini painted his image.3 My recreation of Panini’s painting shows an important change in the cityscape of this antiquated city, demonstrating how my photographs, in addition to Panini’s paintings, can serve as a record of the history of this city.

Another successful photograph was of Panini’s painting of the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls (Fig. 5). My recreation of this painting shows that this basilica remained largely unaltered from the 18th century to today, except for the ceiling (Fig. 6). In Panini’s image, the ceiling portrayed is the wooden cross-beamed ceiling of the original Early Christian church. However, in my photograph, it is easy to see the more Baroque style stucco ceiling that was added in the 19th century (Fig. 6).4 Again, this photograph was able to capture the changes in this building by using nearly the same angle and lighting that Panini incorporated into his painting.

This project has served to add to the artistic record that Panini created of Rome. While some of the images are not perfect, due to Panini’s fantastical landscapes and fish-eye composition, many of the photographs I was able to capture provide an accurate and historical record of the progression of the cityscape of Rome. There is definite room for more research into each of these recreations, as each photograph tells its own story about the immense history of Rome, a history that will be allowed to come to light because of the completion of this project.

References

- Ferdinando Arisi, Giovanni Paolo Panini 1691-1765, (Milano, Mondadori Electa: 1993), 63.

- Ibid., 23.

- Armin Wirsching, Obelisken Transportieren Und Aufrichten in Agypten Und in Rom (English Edition), (Berlin, Books on Demand: 2013), 113.

- Claudio Rendina, Enciclopedia di Roma, (Rome: Newton & Compton: 2000), 867–868.