Sarah James Dyer and Professor Martha Peacock, Art History and Curatorial Studies

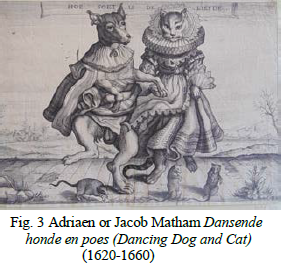

Although some scholars think that Skating Owls (1620-1660) by Adriaen van de Venne (Fig. 1) is solely a lighthearted piece, I have found that through his use of iconographic imagery and well-known proverbs, van de Venne was able to generate a work of art intended to portray a moralizing message condemning the vice of adultery and warning the male audience about the dangers of cunning women. It was imperative for my thesis to see the artwork in person to conduct further research and gain a greater knowledge about the artwork’s purpose. Very little is known or has been published on Skating Owls, but through my field study on the original piece and print, I have found evidence which strengthens my original argument.

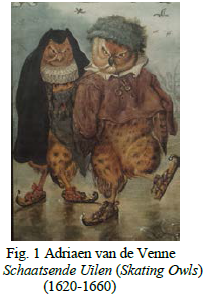

After eight months of thoroughly researching secondary sources, I decided to confirm my theory about this artwork by travelling to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and to the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen to view the primary sources. The former museum houses a surviving print of the painting (Fig. 2) along with another print from the same series called Dancing Dog and Cat (Fig. 3). The Statens Museum for Kunst is the home of the original Skating Owls. I had multiple results from my study, which was conducted through close examination and comparative analysis. First, I will discuss some of my results from studying these prints. I will then discuss the outcomes I found by examining the painting in Copenhagen.

Upon examination of the print Skating Owls in person, I discovered relevant evidence that strengthened my argument. First, after close inspection I found the cracking ice to be more prominent than in photographs that have been taken of this print. This distinction solidifies the intended portrayal of the proverb Ic sta op een krakende ijs (‘I stand on cracking ice’), which means: things are going wrong with me.1 The cracking ice emphasizes the trouble that both owls face: the male owl is in danger of having an unfaithful wife and the female owl is in peril of drowning eternally for her sins.

Next, I made significant finds in comparing Skating Owls with Dancing Dog and Cat. In linking this piece with Skating Owls, one sees several similarities in the iconography. The body positioning of the cat and dog are similar to that of the owls, with the female behind the male. This alludes to a proverb regarding adultery called the Blauwe Huyck, which describes a woman hanging a blue cloak over her husband, making him unable to see her adulterous ways.2 In Dancing Dog and Cat the dog wears a cloak that gives reference to this – again emphasizing her adulterous actions.

The similarities continue with the rats seen at the forefront of the Dancing Dog and Cat suggesting the Dutch theme of promiscuous women (sometimes in the guise of cats) catching men (often portrayed as rats or mice) in traps. This common motif is also seen in Skating Owls with the rats around the neck of the female owl, but this rattish imagery is further accentuated in Dancing Dog and Cat by the female being in the form of a cat – the devious animal that catches rats.

The next similarity between the two pieces is the clothing. Both the male owl and dog are dressed in peasant’s garb. The dog wears a lower-class fur cloak while the owl wears a fur cap and plain tunic. To juxtapose this base clothing, the cat is modeled in an upper-class gown and a millstone ruff (frilled collar). Likewise, the female owl is displayed in a millstone ruff and a hoyke (a headdress worn by the upper middle-class). This separation of classes signifies the theme of unequal lovers; imbalanced partners shown separated either by age or by costuming to give a warning against this type of relationship.3 This contrast is shown further with the expressions on the male figures – they seem to be clueless or uneducated – while their female counterparts have an air of control in each scene. This continues this rift between the two relationships.

After studying these prints, I visited the original piece, which led to a greater discovery – the painting was in color. Each time I found the original piece in a book, on the web, or even on the Statens Museum for Kunst’s website, it was shown in black and white. Even though this may seem like an insignificant find, this detail provided more support for my argument. The coloring of the piece goes along with the colors of peasant and upper class clothing from a book of water colors that van de Venne compiled. The hues of the fur caps, tunics, hoykes, etc., used in the watercolors matched those of Skating Owls, thus solidifying the separation of classes between the characters.

From my travels, I have found the additional information that I needed in order to pursue this topic for possible publication. In conclusion, van de Venne used many strategies in order create a didactic image for the viewers. He employed exaggeration and ridicule to show that these owls were not united, but that they were being driven apart through sin and folly, especially on the part of the female owl. Van de Venne didn’t outwardly show a couple where the wife had been unfaithful, but through satirizing the piece by use of known iconography of the time, and popular parables, he was able to convey a piece to warn people of other’s vices and their own grievances.

References

- D. Bax, Hieronymus Bosch: His Picture-Writing Deciphered (Rotterdam: A. A. Balkema, 1979), 18.

- Wolfgang Mieder, The Netherlandish Proverbs (Burlington: The University of Vermont, 2004), 73.

- Alison G. Stewart. Unequal Lovers: A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art. (New York: Abaris Books, 1977), 82.