Nicole Ashley Vance and Dr. Heather Belnap Jensen, Art History and Curatorial Studies

Introduction

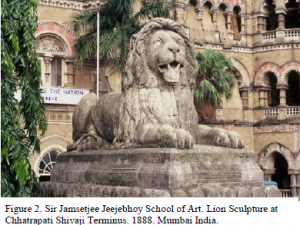

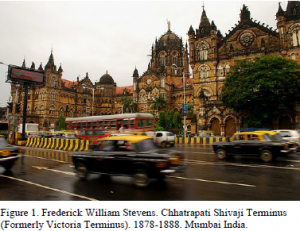

The seaport of Bombay is often referred to India’s “Gothic City.” Reminders of the British Raj are seen throughout South Bombay, embodied in Victorian architecture and sculpture. In the heart of the Bombay lies the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, a massive, towering railway station blending neo-gothic and vernacular architectures of the nineteenth-century (fig. 1). The terminus is evidence of the unique relationship between the British, Parsees, and indigenous peoples during the rule of the British Raj, as European architects worked with Indian craftsmen to create a symbol of ‘progress’ in Colonial India. In keeping with the traditions of gothic revival architecture, the building is heavily ornamented with reliefs and sculpture of flora, fauna, allegories, and government officials. However, these Victorian elements have an Indian flair, as native animals, vegetation, as well as known members of the British Raj and Bombayites are depicted (fig 2). Although some ornamentation was designed by the building’s architect, Frederick W. Stevens, most were created by students of the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art in Bombay under the direction of John Lockwood Kipling. Much research has been done on the construction of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus in recent years as it was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2004.1 However, little research has been accomplished on the decorative sculpture of the railway terminus. I argue that the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus must be studied as it reflects the ideological attitudes of nineteenth-century British and Indian craftsman of Bombay. My research examined the pictorial elements of the railway terminus in terms of their original contexts: the Raj’s educational reform in India, the influence of the Parsees in nineteenth-century Bombay and the use of Indian motif and subject matter.

Methodology

I first began my study of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus by exhausting the existing research to the best of my ability through interlibrary loan. I was able to locate and receive rare books, scans of photographs, as well as doctorate dissertations on nineteenth century Bombay. Because of the nature of the structure, there is significant scholarship on its construction and history, however there was little to discover pertaining to the statuary. I then contacted the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya Museum, Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum, and the Sir J.J. School of Art of Mumbai to know all the necessary precautions for researching in their archives. My faculty mentor, Heather Belnap Jensen was invaluable to this process, providing advice for contacting and researching in museums and archives. November of 2013, I traveled to Mumbai and documented the sculpture of the terminus and conducted research in museum archives. To my surprise, the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum featured an exhibit on nineteenth century fashion in Bombay which greatly aided my study of the headwear of many of the statuary. I was also able to make contacts at many museums in Mumbai which proves valuable to future research. Even walking through the winding streets of colonial Mumbai was extremely beneficial, because I was able to document public statuary also created by the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art—unknown to most academics.

Results

By researching within the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya Museum, Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum, and the Sir J.J. School of Art of Mumbai I discovered many primary resources that I would have been unable to find without traveling to Mumbai. I also was able to present my findings at Brigham Young University’s Primitivism Symposium, as well as Art History’s Senior Thesis in April of 2013.

Discussion

There is definitely room for further research, because in addition to the sculpture of the terminus, I found other sculpture by the same students in the surrounding structures of Crawford Market, Elephantna University, and the Municipal Building. These buildings are different in purpose and have unique decorative sculpture and statuary. It is my hope that the sculpture should be studied as it will lead to its preservation. I anticipate utilizing my research on the decorative sculpture of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus as my master’s thesis.

Conclusion

I discovered that through the ornament and sculpture of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus that the ideological attitudes of the nineteenth-century British and Indian craftsmen of Bombay are expressed. Through the Raj’s educational reform, an intervention occurred in Indian art, guiding ‘native’ tastes. The Art Schools of India functioned as houses of mimicry, where Indian craftsmen were taught and chose to imitate European traditions of sculpture to gain favor with their British instructors and the Raj. The Raj was not the only controlling influence in nineteenth-century Bombay. The influence of the Parsees is seen in their philanthropy to the arts and portraits on the terminus. The Parsees served as intermediaries between the British and the indigenous populations in Bombay. Thus they were often chosen to represent India abroad. Through this selection Parsees had a hand in the arts and crafts shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Through this exhibition, Indian arts and crafts were made known to the British public. Indian pattern and motif served as inspiration for may British designers who saw these new designs as a means to improve Victorian sensibilities and revive their own artistic traditions. Animals served as a means of imperialism, not only at the Exhibition, but also as decorative sculpture on Museums in London and railway stations in India. It is my hope that these valuable sculptures will be well preserved as they give great insight into the Raj’s art education, influence of the Parsees in nineteenth-century Bombay and the interchange of the decorative pattern between the India and Victorian England.